1. Titles of respect

My former principal at Logos School, who's Canadian, went by Dan. Just Dan. This wasn't that weird for the North Americans on staff, but it was unthinkable for our Cambodian colleagues, who insisted on calling him "Mr. Hein" since English doesn't use many titles. I was confused when I first arrived because Dan always referred to an older Khmer woman on staff as "Nakru (Teacher) Chantorn." She was one of the only Logos employees who was not a teacher: she ran the school office. But I learned that it was simply a term of respect reflecting her age, status, and longevity at our school.

It starts young. Parents make their younger children add "Bong" (Older Sibling) to the names of their older children. But it doesn't stop with kids. Anytime you ask about desirable traits in a spouse, respect for elders/superiors always comes up. And it's rare to call someone, even a non-relative, by their first name if they're more than a few months older: there are dozens of titles ranging from the basic "Bong" to some much more specific ones. This is deeper than just words; at a training last month, a Cambodian told my American colleague, "People here want to hear from you because they respect your white hair."

In fact, Khmer rarely uses the words "I" or "you." Rather, people define themselves in relation to the other speaker. So I could call myself "oun" (younger sibling) or "khmuy" (niece/nephew) when speaking to someone older, but "bong" or "ming" or something else when speaking to someone younger. I'm still bad at this, but I'm trying to reciprocate it more when I hear others use these terms with me.

2. Gestures and positions

The classic Cambodian gesture when saying hello or goodbye is the sampeah, palms pressed together while bowing slightly. But there's more than one way to sampeah, as this picture illustrates. The height of your hands literally reflects the other person's status, often in relation to yours. This gesture is linked with similar ones in Thai, Indian, and Indonesian culture, to name a few.

That's not the only time that height corresponds to status. Another American told me yesterday that she was recently sitting on the floor during a Khmer lesson, while her tutor sat in a chair. The tutor interrupted the lesson to say, "I'm sorry, I know you don't care, but this is too weird for me. I can't sit higher than you. You're older and my employer."

3. Standardized lesson plans

Even America's name is decentralized: United States. And every American has heard that any power not explicitly assigned to the central government belongs to the states. In cases like education, local government, school boards, and individuals all bear influence on a given student's education. Some people push for standardization to ensure equal quality for all students, but many others advocate differentiation to give a voice to local stakeholders closer to the situation of each school or classroom.

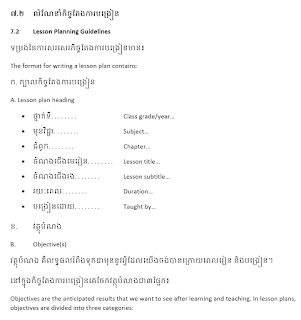

In Cambodia, there are no elective courses, just two tracks (math/science vs. humanities) that somewhat affect high schoolers' schedules and 12th grade exit exam. There are no school district calendars because the whole nation is on the same calendar, (At least in theory... I've heard that rural schools sometimes unofficially extend the holidays, telling students, "Eh, let's take another week.") And every teacher learns the exact same format for lesson plans, which includes a heading with the lesson title and subtitle, among other things, and allots 2 minutes at the beginning for taking attendance. These may not be used daily, but anytime they have to submit a lesson plan, it must follow this format exactly.

This standardization made for an interesting conversation with my co-speaker, Rumny, when we planned our talk on Khmer vs. US lesson plans for earlier this month. I told her there was no such thing as a "US lesson plan" per se, but lots of different tips and templates that various American teachers used. Rumny was baffled. "You mean everyone just makes up their own design?" In response, I googled "American lesson plan template" to make sure I wasn't missing something. I found only 3 results, none of which was relevant.

4. Flash card placement

Many countries have centralized education systems: France and Austria come to mind. But in Southeast Asia, teachers' deference to authorities can be extra pronounced. I recently heard a talk by an American teacher trainer, Tom, working in a country neighboring Cambodia. Tom described once giving a seminar on teaching English using flash cards, where at the end a local teacher raised her hand.

"You told us to hold the flash cards over our heads, but we

learned in teachers' college to hold them to the right of our faces. Which one

should we do?"

Meanwhile, Tom - like all the teacher participants, sitting at the students' desks and listening - could see the problem. In the crowded classroom, many students had an obstructed view of the teacher's face and could only see the flash card if it was over her head! Tom pointed out to me and the other conference participants that as the highest authority in their classrooms, it could appear shameful for teachers to raise a flashcard over their heads. However, when teachers had students hold flashcards during their lessons, Tom noticed that the students all knew what to do. They raised them high above their heads without hesitation! I don't know if Cambodian teachers have a "proper" placement for flash cards, but it wouldn't surprise me.

5. Patron-client relationships

This is a complex issue that I can't fully address here. But

patron-client relationships are a bond that goes deeper than just a

cut-and-dried transaction. They could be between:

- employer and employee

- government official and residents

- a wealthy person and their poorer relatives

6. Prayer

This point ties in with #1, titles of respect. Khmer doesn't

conjugate verbs according to person or tense (I go, she goes, we went, they

will go) but it does have levels of formality to its verbs, which I suppose is

a bit similar. Royalty/divinity, monks, elders, equals, and

children/animals all have completely separate words for actions like eating.

(The fact that royalty and divinity are lumped into the same category, while

children and animals are together in a different category, also tells you something.) The respect attached to titles and verbs made it really fun for

Bible translators, since Hebrew and Greek aren't organized by hierarchy in this

way.

When Christians pray, they always use royal/divine language, just like Buddhists would use for Buddha. So not only the titles and verbs,

but also the body parts, are completely unrelated to the words used to describe

ordinary people. Jesus (Preah Yesu) doesn't have regular hands (dai),

he has divine hands (preah hoah). He doesn't speak (niyay),

he has a divine word (mien preah bantoul). This makes prayer a mouthful

and scary for me to do out loud in front of a group. But it also reminds me of

God's glory and power. He is not like us. He is far greater.

Last week, in an online meeting, I listened to a French teammate

pray aloud. I was struck by how French prayer uses the familiar tu form

for "you," just as English used to use "thou," which

now sounds old and stodgy but used to be the familiar form you'd use with close

friends and family. His prayer made God sound so near and tender.

My teammate's prayer was a great reminder for me that both are

true. God is the pinnacle of every hierarchy - and He's the humble servant who

was born in a manger and washed the disciples' feet. He reigns over all the

universe - with the compassionate presence of a mother. At Christ's feet every

knee will bow - the feet that were pierced in the most humiliating of

executions. He commanded Christians to honor our human authorities - and He

befriended the lepers, the prostitutes, those with no power or status.

God doesn't pick sides in the fight between hierarchical and

egalitarian cultures. He fulfills them both perfectly and transcends them. At

their best and most beautiful, both echo His glory and goodness.